If you would like to explore minor keys, I suggest starting with these three exercises.

Exercise 1 - Choose a major scale. Then flat notes 3 and 6.

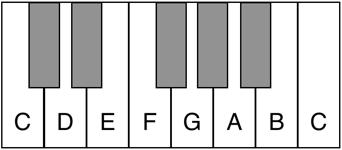

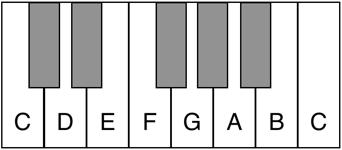

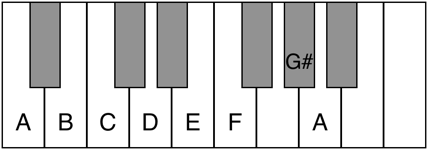

Most people are familiar with the key of C major, so let’s begin there. The C major scale looks like this.

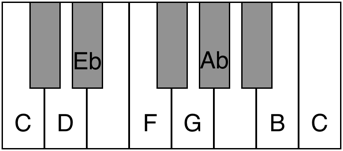

When we flat notes 3 and 6, it looks like this.

But more important than how it looks is how it sounds. It would be a good idea to play all kinds of melodies in this scale. Play recognizable melodies you know in C major. Then flat notes 3 and 6 and play the same melodies again. Or you can improvise melodic lines. Start on note 1, jump around for a while, and then end on note 1.

Okay, let’s talk music theory for a minute. This exercise is known as playing in the "parallel minor.” We use the word parallel to indicate that we haven’t changed the original note 1. It’s still C.

So the key of C major has a parallel minor key: it’s the key of C minor. (And the key of C minor has a parallel major key: it’s the key of C major.)

Playing in the parallel minor is fairly easy—just flat notes 3 and 6. The next exercise takes a little more thinking.

Exercise 2 - Choose a major scale. Find note 6. Renumber the notes with note 6 as the new note 1. Then sharp note 7.

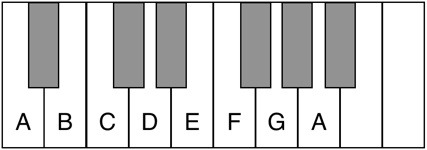

Again, starting with the C major scale, note 6 is note A. We’ll drop down a couple notes to the nearest A and start there.

Then we sharp the new note 7. So G gets replaced by G sharp.

Again, the challenge is to play melodies using this scale. Play until you can hear these notes in your mind. After playing for a while, here are some observations to consider.

First, although this collection of notes is not the same as in the previous exercise, the notes have the same relationship to each other. (This minor scale is exactly like the one in C, but every note has been transposed three half steps down.)

Second, this minor key, A minor, is called the “relative minor” of the original C major scale. The key of C major has a parallel minor (C minor) and a relative minor (A minor).

Third, this minor scale, before we raised the G to G#, was the Aeolian mode (sometimes called “natural minor”). When we raise the G to G#, we call it “harmonic minor.”

Okay, stop for a minute.

One of the difficulties of learning new material is that if too much information goes by in a short time, it’s easy to feel lost. So as not to feel confused or lost at this point, let’s say it again in as simple a way as we can.

As a songwriter, one of your goals is to get familiar with the major scale. There are 12 different notes on the piano, and you can choose any one of them to be note 1, which means there are 12 different major scales you can learn and use.

Each of these 12 major scales can be turned into a harmonic minor scale just by flatting notes 3 and 6. That’s it. If you can play a major scale, and if you can flat notes 3 and 6, then you can play both the major and harmonic minor scale for that particular note.

So that means you would eventually be familiar with 12 major scales and 12 minor scales. Each of the major scales would have its parallel minor.

Now we have to find the relative minor. It’s always three half steps down from the major key in question. For example, if you play a D major scale, you can count down three half steps to the note B. B minor will be the relative minor for D major.

(You can find the notes for B minor in two ways. If you already know the B major scale, then flat notes 3 and 6. Or you can use the notes in the D major scale. Find note 6. Call it note 1. Sharp the new note 7.)

Exercise 3 - Choose a major scale. Play the chord progression I - IV - V - I. Flat notes 3 and 6 wherever they occur. Play i - iv - V - i.

Many songs have been written using the three chords I, IV, and V. In the key of C major, these are the C, F, and G chords. In the key of G major, these are the G, C, and D chords.

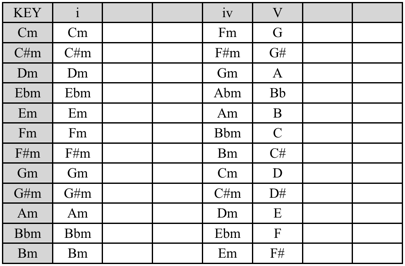

When you switch to the parallel minor key, flatting notes 3 and 6, the I chord and the IV chord become minor chords, but the V chord stays major. So in the key of C minor, you will be playing i - iv - V as Cm, Fm, and G. In the key of G minor, you will be playing Gm, Cm, and D.

We can list the i - iv - V chords in a table like this.

When playing i - iv - V - i on a piano or keyboard...

When you play i - iv - V - i on a piano or keyboard, there is a simple way to play it that isn’t best, and there is a better way to play it that isn’t quite as simple. But it’s so much better in the long run that it’s worth the time to mention it.

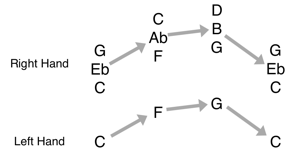

Here’s the simple way. You can just move all the notes in parallel. It’s as if your hands stayed in the same position and then hopped across the keyboard to the next chord. A diagram might look like this.

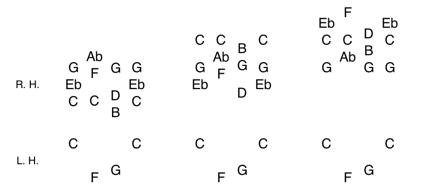

The better way to play it involves learning three different sequences as shown.

You’ll notice that each grouping of chords stays fairly close together, not jumping across the keyboard. Instead the right hand adjusts, opening or closing just a little to play the next chord.

These three ways of playing the progression give a smoother sound. That doesn’t mean you will never play songs that call for big jumps, but it demonstrates that moving to a nearby chord often sounds better than moving everything in parallel.

Time to Review

In this lesson, we began exploring minor keys with three exercises.

First, we played a melody in a familiar major key. Then we played the same melody again with notes 3 and 6 lowered by a half step. This gave us the harmonic minor scale for the key that we call the parallel minor (because it starts on the same note 1).

Second, we started again with a familiar major key. We counted up to note 6. We called note 6 the new note 1 and renumbered all the notes. This scale is called the Aeolian mode, or natural minor. We then sharped the new note 7 by raising it one half step. This scale is the harmonic minor scale in the key that we call the relative minor (because it’s related to the original key, using the same seven notes before we raised note 7).

Third, we played the I - IV - V - I progression in a familiar major key. We recognize that flatting notes 3 and 6 would cause the I and IV chords to become minor chords. So, the progression I - IV - V - I can now be written i - iv - V - i.

We demonstrated that there is a simple way to play this progression on a piano, or keyboard, by keeping both hands in the same position and jumping from chord to chord. But we mentioned that a smoother sound happens when we play the progression in three different places, allowing the right hand in each case to stay close to where it starts, and making slight adjustments in the stretch of the hand to land on the notes required for the next chord in the sequence.

When you feel you understand the concepts presented in this part, move on to Part Fifteen.

OTHER RESOURCES

PDF eBook

The materials presented in Section 1 (Parts 1-12) are available as a downloadable PDF eBook. Click for more information.

Yours To Play It

...free, interactive, chord-exploring MIDI controller app for

Windows computers.

ChordMapMidi

...interactive, chord-exploring MIDI controller app for iPhone.

ChordMaps2

...interactive, chord-exploring MIDI controller app for iPad.

CarolPlayMidi (Christmas Carols and Hymns), DrumMapMidi (basic

drum patterns), and PowerPlay5 (play power chords on iPhone) are

our other iPad and iPhone MIDI controller apps.

______________________

Music Theory for Songwriters is part of MugglinWorks.com

Page was created with Mobirise web theme